the rising and falling, the ups and downs, good and bad in the conservation of north florida and beyond in the sunshine state

Florida is an increasingly desirable place to visit, work and live, and keeping it that way is important to all of us. Yet the attractiveness of the peninsula and the effect of that popularity on the environment illustrates the constant need for balance.

Total visitors to Florida in 2019 were more than 133 million, making Florida the number one U.S. tourist attraction. That figure crashed in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdowns, but it is steadily rising back to pre-COVID numbers.

The website Visit Florida notes that visitors come to the Sunshine State for a variety of reasons—that infamous sunshine for one; mild climate; and outdoor activities such as hiking, bicycling, boating, kayaking, golfing, fishing and equestrian sports. Florida’s fascinating fauna is also a draw—alligators, crocodiles, panthers, sea turtles, manatees, dolphins and at least 516 species of birds. But the benchmark of Florida’s popularity as a tourist location is by far its water.

Florida’s coastline is one of the state’s most distinctive attributes. With 8,436 miles of sandy shores, it is second only to Alaska’s whopping 33,904 coastline miles.

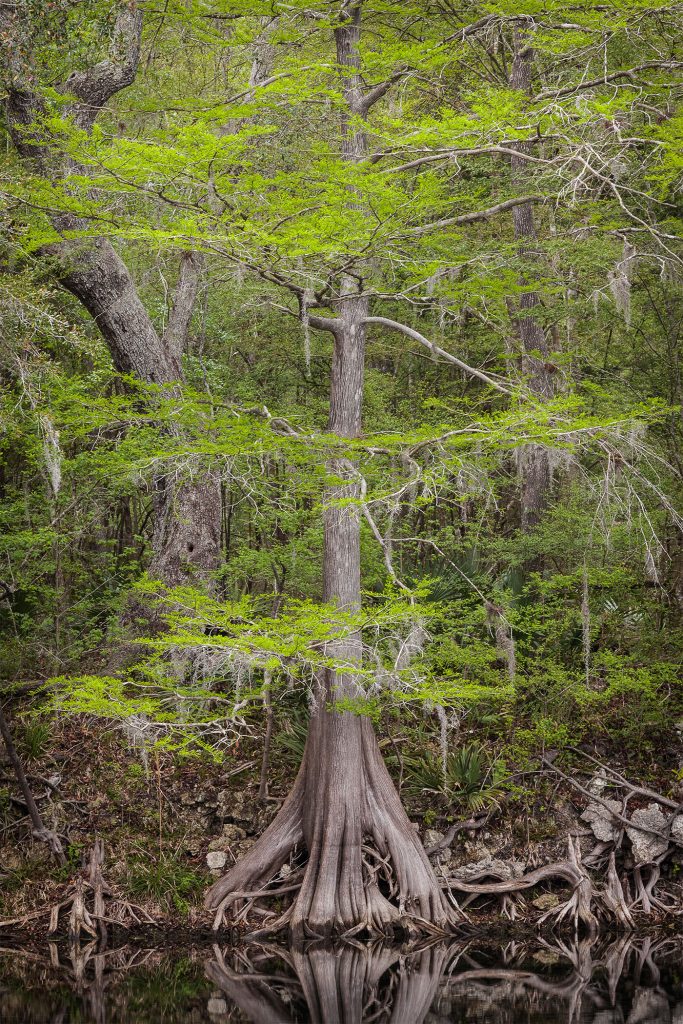

Wherever you are in Florida, you’re never more than 60 miles from the nearest ocean. But salt water is not the only draw. The state has more than 7,700 lakes, 11,000 miles of rivers and 2,276 miles of tidal shoreline. It has more than 700 freshwater springs, 27 of which are classified as first-magnitude springs—more than any other state. Florida has produced more than 900 world fishing records, also more than any other state.

Water inevitably defines the Florida lifestyle. Whether on the coast or in the state’s interior, the relationship of water to the land and its effect on humans are indisputable.

And water draws tourists.

Tourism is one of Florida’s largest industries. Why so many people visit our state affects decision-making about where the state spends its resources. According to a 24/7/Wall St. article reported by UCF Online, out of all the states in the country, Florida has the fourth-largest Gross Domestic Product behind only California, Texas and New York.

But it’s not just visitors flocking to our state. People have been moving to Florida in record numbers, particularly since the pandemic hit and national political unrest has escalated. Florida is ninth in the country for population density. And more people require more resources, which means that as the population increases, the state’s resources deplete more rapidly. This depletion leads to environmental concerns such as water access and quality, deforestation, and loss of biodiversity as humans strip the land of resources to accommodate rising population numbers.

So with more tourists and more new residents, conservation is ebbing to the top levels of Florida’s agenda.

Conservation in U.S. History

In the past 130 years, government has addressed conservation with varying emphasis and success. In 1891 Congress passed the Forest Reserve Act, followed by the Forest Management Act in 1897.

Then in 1901, conservationist, outdoorsman and sportsman Theodore Roosevelt became President of the United States. In 1903, he established a federally protected wildlife refuge at Pelican Island, Florida, the first of 53 wildlife sanctuaries he created. Even from the beginning, Florida led the way in conservation, as Pelican Island set the precedent for today’s National Wildlife Refuge System—the only network of federal lands specifically dedicated for wildlife conservation. This network consists of 550 such refuges and thousands of Waterfowl Production Areas totaling over 150 million acres.

A series of acts followed. The American Antiquities Act was created in 1906, and in 1907 forest reserves were renamed “National Forests.” The Wilderness Act was established in 1964, the Land and Water Conservation Act in 1965, and the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the National Trails Act in 1968. All of these impacted the Sunshine State.

Florida lawmakers themselves have jumped on the conservation bandwagon. As recently as April 2021, they unanimously passed the Florida Wildlife Corridor Act that devotes $300 million to preserving migration paths for animals such as the Florida panther, helping to mitigate isolation and inbreeding.

Positive, lasting change happens when individuals passionately and thoughtfully work to make the world a better place, not just for themselves, but ultimately for future generations. When Floridians work alongside government to find solutions that preserve Florida, the result is a win-win for everyone. A healthy ecosystem raises the quality of life for all—humans and animals.

The Nature Connection

The National Wildlife Federation notes that health and social benefits of nearby nature have clear implications for conservation and the future of urban development. More than 50 studies point to nature-based play as key to developing pro-environmental behavior because it nurtures an emotional connection to the natural world.

For kids, the natural world can be a place of peace, health and inspiration—and can launch a lifetime passion for conservation. Pediatrician Stephen Pont, founding chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Obesity, describes nature as a “stealth health” intervention, saying it acts as both prevention and therapy by encouraging children to engage in health-improving activities without even realizing it.

But nature is important to people of all ages. For children and adults, connecting with the natural world has massive health benefits including easing depression and anxiety, preventing or reducing obesity and myopia, and boosting the immune system. Perhaps most importantly, nature expands the senses and increases wonder.

Research also suggests that healthy urban ecosystems that focus on the natural environment can lead to more cohesive neighborhoods, reduced aggression, lower crime, better social bonding and less violence. A 2019 study published in Health & Place found that parks in low-income neighborhoods lead to a significant increase in “resilience,” a balanced response to stress.

Is it any wonder so many of us turned to nature to cope with the physical and mental challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic?

People’s return to nature during the shutdown has been nothing less than astounding. The Wildlife Management Institute reported a major increase in hunting and fishing license sales, increased visitation to parks and other public lands and recreational areas, and increased outdoor clothing and equipment purchases, among others. New and returning outdoor recreation enthusiasts are generally younger, more diverse, and from urban and suburban households.

COVID changed life significantly for all of us. Yet nature’s constant presence and ever-changing elements are both reassuring and wondrous. Nature’s flow is, simply, something we can count on to entertain, nourish and inspire.

Increased Focus on the Environment

The pandemic response seems to be the icing on the cake to an interest in conservation, biodiversity, environmental protection and ecotourism that has been steadily growing both on a national level and in Florida for more than 25 years. We are becoming increasingly aware that we cannot count on nature to always be there for us.

Strong majorities of Americans believe the government should do “whatever it takes to ensure a healthy environment,” according to Dr. Mark W. Schwartz, professor of Environmental Science and Policy at UC Davis. Schwartz reports that 68 percent of those pooled take time to visit green or blue spaces at least monthly. This interest in nature spans generations, ethnicity and political party.

What motivates individual citizens to action? For some, stewardship of the Earth is a fundamental religious belief. Christians see themselves not as owners but stewards of all that comes into their arena of responsibility—income, assets, property, goods, time, talents, even themselves.

For Jews, the human being is both master and servant of nature, a guardian of property that belongs to someone else.

Muslims stress seven Quranic verses that tie stewardship to the earth and charge human beings with the responsibility of carrying out this trust.

Native Americans are even more tied to the land. They are the land—a relationship not of dominion but a life-supporting, life-creating reciprocity.

Still others are motivated simply by a love of nature in and of itself. But whatever the reason, conservation efforts are becoming more prevalent, especially in Florida.

Protecting the Land

In our area of the state, the Northeast Florida Land Trust (NFLT) works to preserve and enhance our quality of life by protecting north Florida’s natural environment. It acquires land for preservation solely by donation, inheritance, purchase or through conservation easements.

The trust expects to help the state and landowners work out deals to preserve land throughout the region in response to the Florida Wildlife Corridor Act. The Act provides funding to preserve migratory routes within the Florida Wildlife Corridor, which includes NFLT’s Ocala to Osceola (O2O) wildlife corridor project.

The O2O Corridor is a partnership of 24 federal, state and non-government organizations that are working together to conserve and improve the ecological conditions, military buffers and working lands within the 100-mile, 1.6 million-acre corridor. The O2O includes priority lands for the Florida Ecological Greenways Network (FEGN) and is a significant part of the Florida Wildlife Corridor.

If the system of natural landscapes and connector lands is protected, the O2O will continue to provide habitat for Florida black bears and imperiled species like the red-cockaded woodpecker, indigo snake, Sherman’s fox squirrel and gopher tortoise. In addition, iconic Florida ecosystems, including longleaf pine forests, sandhills and scrub, will be protected in the O2O. The corridor also contains the headwaters of outstanding waterways and major recharge areas for the Florida aquifer, which supplies water across most of Florida and to neighboring states. Conserving the land also helps with water quality and quantity.

Public lands compose about 40 percent of the corridor. The remainder is a patchwork of privately owned natural and commercial forests.

Other significant conservation efforts by NFLT during 2021 include:

- Approval in April to add the Big Pine Preserve to the Longleaf Pine Ecosystems Florida Forever project area. This preserve consists of 541 acres in Marion County and is located within the O2O Corridor. It contains one of Florida’s largest old-growth longleaf pine forests. Protecting this land will keep more than a half-mile of lakeshore free from development. It is also close to spring waters and could have water quality implications if not conserved. The lake is a popular location for fishing and water recreation, and preserving it will add more conservation lands for outdoor activities.

- The purchase of preservation land near Egans Creek Greenway for the City of Fernandina Beach. NFLT negotiated the deal to buy 5.25 acres on a tributary to the greenway. The city paid for the land, and NFLT contributed staff time to facilitate the acquisition.

- The purchase of 119 acres in Bradford County as a conservation easement that will ensure the land remains in agriculture production forever. The property, which is a working cattle ranch, is in Lawtey, approximately 1.5 miles west of Camp Blanding. The conservation easement is within the priority area for conservation for Camp Blanding and the Army Compatible Use Buffer (ACUB) program designed to secure buffers around military installations.

- The purchase of 12 acres of land to expand Bogey Creek Preserve as the last link in connecting all the parks in the 7 Creeks Recreation area. The preserve contains habitats including maritime forest, salt marsh and hardwood wetlands, known for supporting species such as gopher tortoise, wood stork, Atlantic sturgeon, shortnose sturgeon and West Indian manatee. Bogey Creek Preserve is NFLT’s first public park and the only one with public access.

- The first Emerald Trail property contract was approved by the Jacksonville City Council on June 22, 2021. NFLT negotiated the purchase of the property at the corner of Kings St. and McCoys Creek Blvd. The properties that the City is identifying for the Emerald Trail Project will alleviate flooding, help restore habitats, help provide a more resilient ecosystem, and link 14 historic neighborhoods. NFLT is also working closely with Groundwork Jacksonville, the leader of the Emerald Trail Project, as well as the National Park Service and Environmental Protection Agency.

Advocating for the Water

Water conservation projects in north Florida have had a significant impact on our area. The protection of the Suwannee River Woodlands, for example, has been one of the largest conservation efforts of a wildlife corridor east of the Mississippi River. Approximately 50 miles west of Jacksonville lies a vast wilderness known as Osceola National Forest. Part of a great matrix of forests and wetlands in Florida and Georgia, Osceola connects with Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge to the north, and together they form the headwaters of the iconic Suwannee River. Fed by blackwater creeks and clear freshwater springs, the Suwannee ultimately flows into the Gulf of Mexico and Big Bend Seagrasses Aquatic Preserve just offshore. This region has been a priority for conservation since the 1980s because it serves as a critical source of water for North Florida communities.

St. Johns Riverkeeper is the chief advocate and voice for the St. Johns River. The agency holds regulatory agencies and those polluting the river accountable, and identifies and advocates for solutions that will protect and restore the river.

One current issue on which the nonprofit is focused is reconnecting the Ocklawaha, Silver and St. Johns rivers. The St. Johns Riverkeeper is part of the Free the Ocklawaha River Coalition, 60 organizations representing thousands of members from across Florida and beyond. Its mission is to restore the Ocklawaha as a free-flowing river, which will reconnect the Silver and St. Johns rivers. The largest tributary of the St. Johns River, the Ocklawaha and its springs and wetlands were submerged when the Rodman Dam (now called the Kirkpatrick Dam) was built in Putnam County in the late 1960s as part of the failed Cross Florida Barge Canal. Breaching this dam will re-establish access to essential habitat for manatees, bring back migratory fish, reconnect three river ecosystems and historic Silver Springs, and restore a lost riverway for anglers and paddlers from the Ocklawaha to the Atlantic.

Similar to St. Johns Riverkeeper, Matanzas Riverkeeper is a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting the health of the Guana, Tolomato, Matanzas watershed. The Matanzas watershed contains some of the last places in northeast Florida where the water is clean enough to harvest and eat shellfish without

risking illness.

Giving Land

But conservation efforts in Florida are not limited to organizations and government. Individuals are also taking the reins. Philanthropic donations are one way some people are making a difference.

Five years ago, Ben and Louann Williams approached the NFLT to help preserve their 3,562 acres in perpetuity. After much work, in January 2020, the organization facilitated the purchase of a conservation easement on Wetland Preserve in Putnam County with funds from the Florida Forever program. The easement will allow them to continue to own the land while ensuring it will never be developed.

“The Williams use their land as a working forest and educate others about its ecosystem benefits, but they also wanted to make sure the land remained free from development for future generations,” said Jim McCarthy, president of NFLT. “We had a few options over the years but none of them panned out. We are grateful to the Florida Cabinet and the Division of State Lands at the Department of Environmental Protection for realizing the need to make sure this land remains a preserve.”

The land is mesic flatwoods, mature creek swamps and a smaller area of dry sandhills. It produces fiber and wood and also serves wildlife, protects water resources and benefits native plants. The Williams, who were named Florida Landowners of the Year by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, are also permanently preserving the right for the Florida National Scenic Trail to use its current trail across their land.

Wetland Preserve is a critical link in the Ocala to Osceola (O2O) wildlife corridor and is located within the Etoniah/Cross Florida Greenway Florida Forever project. NFLT identified it as a preservation priority property in 2015, and in 2017 helped move it to the top of the list for the Rural and Family Lands Protection Program before that program was defunded. NFLT then identified the Florida Forever Program as a funding option for the conservation easement and assisted the family through the process while helping the state understand the property and execute due diligence.

The Etoniah/Cross Florida Greenway Florida Forever project contains 952,180 acres of land identified for conservation in central Putnam County extending to the Ocklawaha River. The project was approved in June and is ranked number 11 in the critical natural lands project category for the state. The conservation easement on Wetland Preserve moves the project closer

to completion.

Local Property Donations in Honor/Memory of Others:

Robert R. Milam Jr.—Patricia Milam Sams, 91, gave a significant donation in honor of her big brothers, who is also still living.

Noble Enge Jr.—Before his passing in 2010, Noble Enge Jr. spent his life exploring the outdoors, both on land and in the water. He believed in land preservation, and after his passing, his sisters deeded a 411-acre property to NFLT to be permanently preserved.

Renate and Joe Hixon, Ed Burr, Diane Joy Milam Dennis—In 2012, NFLT began acquiring all remaining privately owned lands on Big Talbot Island’s 1,095 acres. This work was made possible through a generous gift by Diane Joy Milam Dennis, sister of Arthur Milam, who wanted to preserve the land for their children and grandchildren because of their memories vacationing there every summer growing up. Today, nearly all of the island is permanently preserved.

Grants

Grant donations are also valuable to conservation efforts. A 2:1 matching grant from the Delores Barr Weaver Legacy Fund, for example, helped complete NFLT’s fundraising goal to pay back a loan acquired to purchase a portion of the Little NaNa Dune system in historic American Beach.

The owners of the property had been trying for years without success to find some entity to acquire and preserve the land. They were skeptical that it would ever happen and last January gave NFLT only 90 days to buy the land. NFLT took a leap of faith and took out a loan to buy the property.

“We typically fundraise before the purchase, but this situation required us to close on the property within 90 days,” said McCarthy. “We have had one year to raise the money to pay off the loan. We have been asking foundations, businesses, government entities and individuals to donate.”

NFLT has since received donations through its Amelia Forever Campaign from foundations like the Delores Barr Weaver Legacy Fund, businesses, government entities and individuals, including an anonymous $500,000 donation, to pay off the loan. It now owns the land outright.

“We wanted to protect this historic community and its natural benefits for the good of the wildlife that depends on it. We also wanted to protect the sense of place that rests in the memories of many generations of families who vacationed in American Beach at a time when they were prohibited from beaches all across this country,” said McCarthy.

NFLT closed on the property on January 13, 2021, to honor the legacy of MaVynee Betsch, known as “The Beach Lady,” who would have been 86 on that day. Betsch was a champion for the preservation of American Beach.

“Delores Weaver’s matching gifts have been critical to our organization in opening up access to new donations,” McCarthy said.

Entrepreneurial Conservation Efforts

Some entrepreneurs also are heeding the conservation call. Ortega resident Jeff Meyer and his startup business, Johnny Appleseed Organic, is a good example of a citizen’s environmental call to action. He launched the company’s debut product, an eco-friendly garden fertilizer called ClimateYard™, in April 2021.

Lawn fertilizers that run off into our rivers are a leading cause of toxic algae blooms. When traditional nitrogen fertilizer is applied faster than plants can use it, soil bacteria convert it to nitrate. Water-soluble nitrate is flushed out of soils in runoff, where it pollutes groundwater, streams, estuaries and coastal oceans, and causes algae blooms. Toxic algae blooms lead to fish kills, skin rashes, unappealing odors and accumulation of foam and shoreline scum.

“People are putting things into their yard that drain into the river and the Intracoastal Waterway,” Meyer said. “We’re destroying opportunities for the plants andanimals to thrive. If we get rid of septic tanks and fertilizers, we will have a completely different environment.”

Meyer talks about three “kingdoms” in the environment—plant, animal and fungal. ClimateYard™ works with the fungal kingdom. It replaces conventional fertilizer with a blend of beneficial bacteria and fungi that fix atmospheric nitrogen in the soil and improve the availability of phosphorus that’s already there. Combining cutting-edge microbiology with plant nutrition, the product’s living organisms build up, so that over time you can use less and less of it to fertilize your yard.

The prime job of fungi is to sustain the natural world. Along with bacteria, fungi are important decomposers in the soil food web. They convert organic matter that is hard to digest into forms other organisms can use. Their strands physically bind soil particles together, which helps water enter the soil and increases the earth’s ability to retain liquid. That means yard owners will water their yards less over time, saving water on multiple levels.

Meyer uses no pesticides or herbicides in his Ortega yard. Instead, he uses soil amendments and 100-year-old bacteria and fungi.

“I’m putting nitrogen-fixing bacteria on lawns instead of nitrogen that is in conventional fertilizer,” said Meyer. “My goal is to reactivate the fungi we’ve killed by using fertilizer over the past century.”

“As I walk through my yard and see all the butterflies, I’m reminded that most people don’t really understand what they’re killing when they spray pesticides. There’s so much they are killing that they would really enjoy. It is a shame.”

Protecting the Environment

A number of organizations in our area work tirelessly to protect our region’s natural resources. The following four are perhaps best known examples to North Florida residents.

Sierra Club is a national organization dedicated to enjoying, exploring and protecting the planet. It is the oldest, largest, and most influential grassroots environmental organization in the United States. The Northeast Florida Group organizes and participates in outdoor adventures, environmental education and local environmental activities.

Nature Conservancy works to conserve the lands and waters in Florida. The nonprofit owns and manages approximately 55,159 acres in Florida including four preserves that are open to the public.

Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve encompasses one of the last unspoiled wetlands on the Atlantic Coast, including 6,000 years of human history, salt marshes, coastal dunes and hardwood hammocks. It sweeps from Fort Caroline to Kingsley Plantation.

Duval Audubon Society is one of 44 chapters of Florida Audubon and a member of National Audubon. Its mission is to connect people with nature, conserve and restore natural ecosystems, and focus on birds and other wildlife.

Conserving for the Future

Ebb and flow, rising and falling, ups and downs, good and bad, give and take—these are all part of the rhythmical cycle of life. For Florida, tidal motions are a natural movement of water over land, currents, gravitational pull and seasons. Our lives often mimic the flow of the tides, and are evidence of the ways humanity affects environment.

Ultimately, it is all about balance. Balance in development, balance in protection, balance in people coexisting with nature. While there is no such thing as a perfect world for everyone, a balanced community—and world—is an admirable pursuit, and one that Floridians are leading in the United States today. As the popularity of The Sunshine State and the resulting effect on our environment ebb and flow, may we endeavor to make our treasured state ever more protected, safe and beautiful for future generations.