Offering solace to surviving families of unsolved homicide

He may not wear a glistening robe or have the feathered wings of an angel, but for many families who are suffering from the unsolved murder of a loved one, Ryan Backmann and his nonprofit, Project: Cold Case, seem heaven-sent.

Established by Backmann three years ago, the organization has the ambitious goal of publicizing as many unsolved homicides from throughout the United States on its website and through social media as it can. It is Backmann’s hope that by drawing attention to investigations gone cold, families with murdered loved ones may find comfort and more cases will be solved.

“Our goal is to share the cases and offer support to the families,” said Backmann, adding he hopes witnesses will come forward to submit information on the website or give tips, which he passes along to Crime Stoppers or law enforcement. So far, 10 cases showcased on the Project: Cold Case website have come up with arrests.

“There’s no other organization out there on our scale that’s doing this for unsolved victims,” he said.

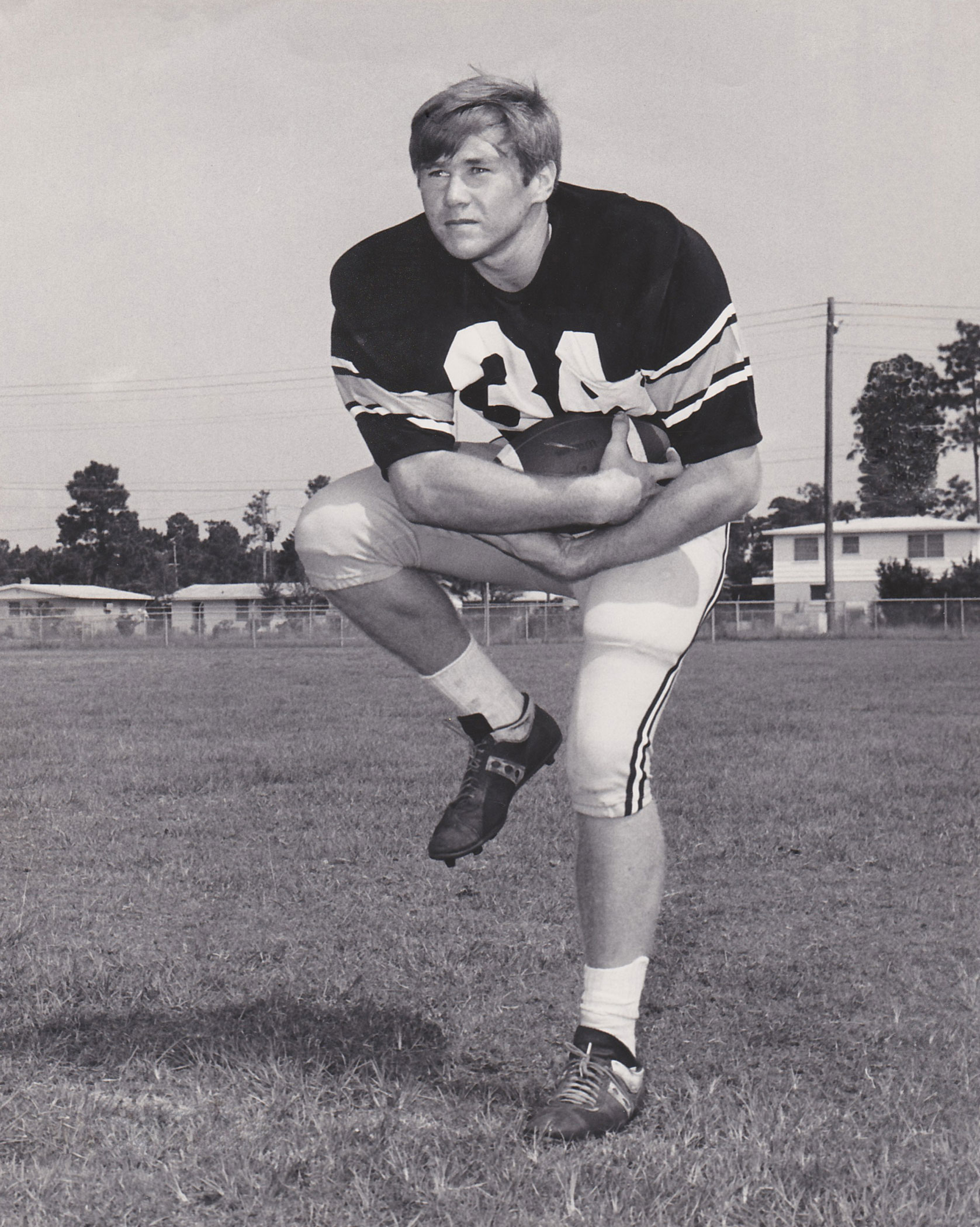

Although Backmann, a former project manager for an architectural firm, never envisioned running a nonprofit prior to setting up Project: Cold Case, he finds he is uniquely qualified for the work – he is a homicide survivor himself.

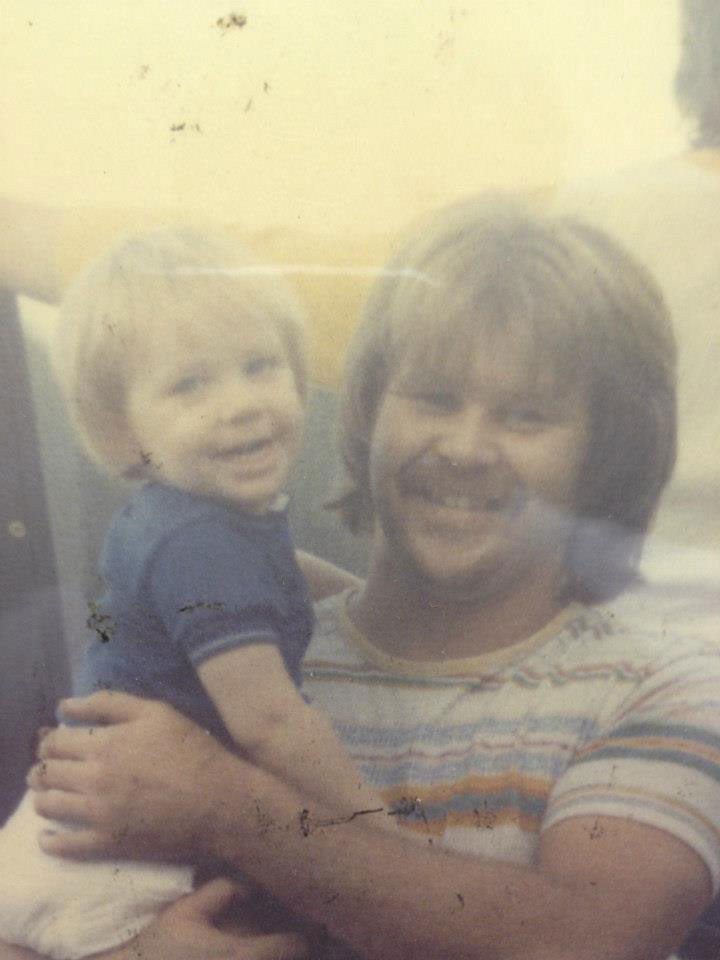

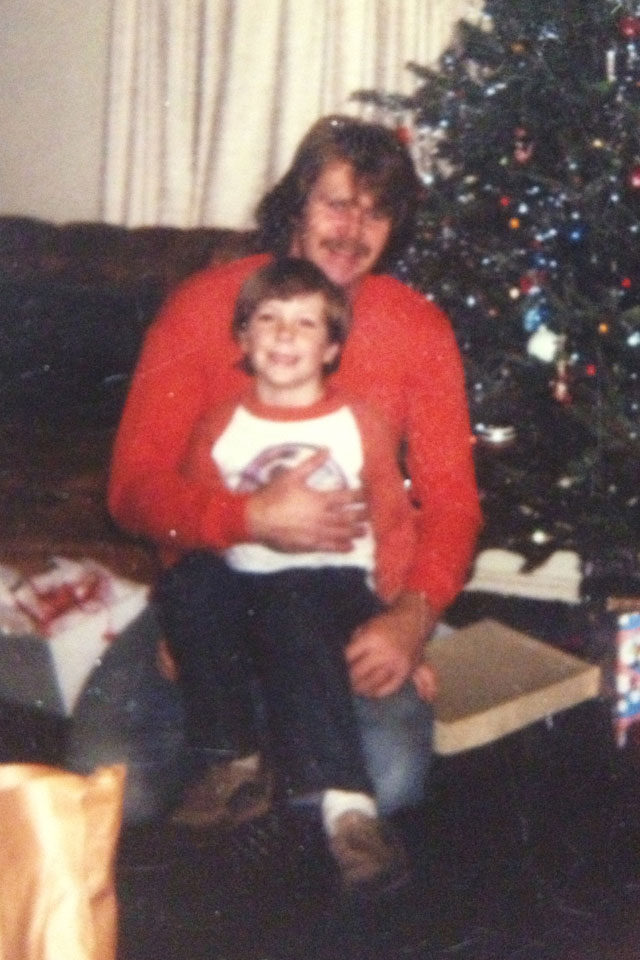

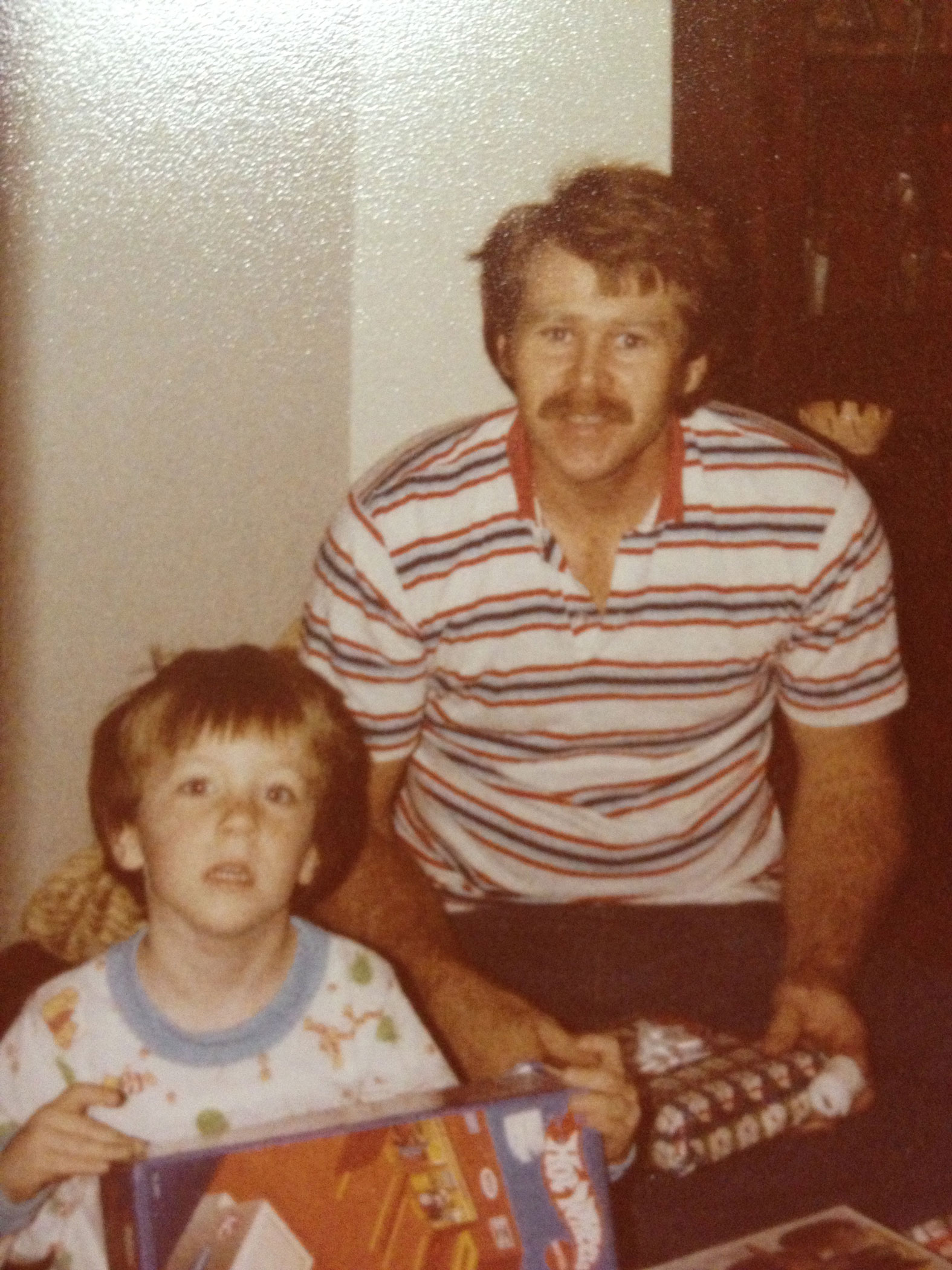

Backmann’s life changed forever on a Saturday afternoon in October 2009. While he was getting ready to visit friends for an afternoon of watching football, he and his wife, Valerie, were shocked to find detectives at their door with terrible news – an unknown assailant had murdered Backmann’s father, Cliff, as he was doing renovation work in a one-story office complex on Bonneville Road.

“My dad just happened to be there by himself,” recalled Backmann. “The detectives think someone happened to be walking through the parking lot, saw my dad working by himself, vacuuming up drywall dust. Dad probably didn’t notice the guy come in. He put a gun to my dad’s back and shot him. The speculation is that he may have startled my father, who jumped, and the gun went off. The guy took my dad’s wallet, but Dad lived long enough to call 9-1-1 and give a description of him before he lost consciousness. Dad basically spent the last seven minutes of his life on the phone with the 9-1-1 operator trying to describe his killer,” he said, noting the description did not give detectives much to go on – a black man in a red shirt.

In the months following the murder, the despairing Backmann struggled at work, eventually losing his job. On top of that, seven months later his beloved stepmother, Jane Tuttle, died of cancer, having lost her desire to fight the dreaded disease due to her partner’s death. Fortunately, an angel in the form of a nonprofit organization called Compassionate Families, came calling.

Compassionate Families, which has since disbanded, was founded by Glen and Margaret Mitchell after the afterschool murder of their 14-year-old son, Jeff, at Terry Parker High School in 1993. Its mission was to serve the needs of all homicide survivors in Northeast Florida with immediate and long-term support, grief recovery assistance, and life-rebuilding skills through a unique peer-support and counseling program.

By inviting Backmann to its monthly men’s-only support group, a Compassionate Families’ volunteer changed Backmann’s life.

“I knew I needed to talk to somebody,” he said, remembering there were three men who had lost children to homicide in his group. “I was supposed to bury my dad, but not the way I did. All these men had to bury their children, which is way out of balance. I was inspired by them because they had jobs and they were still stewards in the community. Somehow, they had found a way to survive such horrible tragedy. That changed my perspective, and I started volunteering with the organization,” he said.

In addition to running support groups, Compassionate Families held vigils, ran day camps for children who are homicide survivors, and served as advocates for families with law enforcement and the State Attorney’s office. Soon Backmann was on the nonprofit’s payroll, helping other surviving families.

Because Compassionate Families mainly supported families of cases that had arrests, Backmann noticed there was a greater need to focus on cold cases. “I decided if I started an organization, I would narrow it down to just unsolved homicides. The families where arrests had been made have resources. I didn’t need to duplicate those services. Nobody was offering resources for people with cold cases,” he said, adding that as a Compassionate Families’ advocate, he already had many contacts with law enforcement and the State Attorney’s office.

Initially self-funded, Backmann started Project: Cold Case in his home while caring for his four-month-old daughter, Mae. Through making a public records request, talking to law enforcement, and asking Jacksonville families if he could post their loved ones’ photos on his website, Project: Cold Case was born. Soon 1,200 cases were listed.

“I didn’t have one family say no. You think no one cares and then suddenly someone calls and wants to put your loved one on a website and social media, so it will draw attention to the case,” he said.

Soon word got out and families nationwide wanted to submit cases. “I couldn’t turn my back on them just because they live somewhere else, but I also can’t provide the same resources as I can for somebody who lives in Jacksonville or Florida. But I want them to know that someone cares. I will do that for anybody who needs our services.”

In addition to posting murder victim’s photos and spotlighting cases on social media and television, the nonprofit assists surviving families by accompanying them to court when an arrest is made, setting up meetings with police, helping survivors to negotiate the maze-like bureaucracy of law enforcement and the court system, offering local and online support groups, and maintaining a cold-case data base with 2,900 unsolved cases nationwide. The data base provides a way for people to submit information about the homicides or provide tips. It also serves a tool for the media and students doing research projects.

“Families don’t know who to call or how to go about getting information,” he said. “I found out quickly this was a necessary and needed organization.”

Project: Cold Case holds two fundraisers per year and is presently soliciting donations so it can fund forensic testing using new DNA technology from Parabon NanLabs to help solve cold cases. “It is unacceptable that a few thousand dollars might be the difference between solving a case and having it remain unsolved,” he said.

Although Backmann considers his nonprofit to be a living memorial to his father, his father’s name is not on the foundation because its mission is greater than just one case. “I’m cautious about making it about my dad because I feel law enforcement did their best with his investigation. It’s not their fault his case isn’t solved. If I spent the rest of my life on my dad’s case, I don’t think that would help me to heal,” he said.

Besides helping himself and others heal, Backmann said the driving force behind his work is public safety. “I love what I do. This is my way to give back to the world – to make it a safer place. I tell people, the guy who killed my dad could be in line next to their wife at the grocery store or live next door to their kid’s bus stop. That’s an unsettling feeling. As long as I’m here, we’re going to work toward finding the killers and getting them off the streets to protect everybody.”